Every morning before he starts work, no matter what the weather, Charlie Connelly takes a flask of tea to the beach outside his home in Deal on the east Kent coast, and goes for a swim in the English Channel.

As a writer of quirky travel books, it was perhaps inevitable that he would eventually write about this busy and turbulent stretch of sea, which separates – and connects – Britain to the rest of Europe. Just 21 miles wide at its narrowest point, it has attracted dreamers who want to tunnel under it, swim it, fly or float over it. And in The Channel, he tells their stories.

He discovers that the first man to fly across the Channel was actually a terrible pilot, and that the Tunnel was first dreamed of by a man with a buttered head and pigs bladders tied to his trousers. He follows Oscar Wilde’s lonely exile in Dieppe, and tells the story of Martha Gunn, a Brighton ‘dipper’ so celebrated for dunking the gentry into the sea that the Prince of Wales gave her free access to the kitchens of the Royal Pavilion. It’s one of those books that makes you laugh out loud, and fills you with entertaining facts that you didn’t know you wanted to know.

Absurdly productive, Connelly writes a weekly column for the New European and has a podcast. He has ghost-written autobiographies with New Order’s Bernard Sumner and the champion jockey AP McCoy. And in his own books he has paid homage to radio and explored his own family history, or undertaken journeys themed around the weather, football, the shipping forecast – and of course Elvis.

Yet none of this comes easy, he says. He loves finding the stories, but the writing? That’s still a challenge.

So how does each book start?

Ostensibly they’re travel books, but they always have a theme of some kind, something that I’m interested in and want to find out more about. There has to be a reason to go somewhere. So I tend to have an overarching theme for books, which then requires me to go to specific places.

Attention All Shipping, the book I wrote about the shipping forecast is probably the best example. There were 31 sea areas, and I had to go to or through them all. So I was going to places I would never otherwise go to like Fair Isle, or Arbroath. You don’t wake up in the morning and think, ‘I’ll go to Arbroath!’

We both live in Deal, on the Channel coast. I’ve lived here 10 years, yet you found lots of stories that I didn’t know. How do you research it?

I tend do too much research, because I’m not an expert on anything. So I always think I have to go that extra mile – literally – to make the story plausible and to make me plausible, as the storyteller.

That’s my favourite bit. Finding a story, then researching it more deeply and finding out things that other people possibly haven’t about these people and events. It’s a really good feeling when you when you stumble on something. It might be a sentence, something in an old book, or even on a website. And you get that feeling of, ‘Oooh! There might be something in this!’

Calais was fascinating, for instance. It’s generally seen as somewhere you pass through on the way to somewhere else. But there’s so much history there. And bizarrely so much English history, because Calais was an English possession for about 300 years.

British people tend to think the refugees all came one way and always have done, but it’s also where British debtors would flee to try and get themselves together. Even Emma, Lady Hamilton, who was Nelson’s partner. She was completely written out of the story after Nelson died. He wanted her to be provided for. But that didn’t fit that the national narrative, with her being married to someone else. So she ended up in Calais, broke. Beau Brummell ended up there too.

Those are the kind of stories I seek out. A travel book is quite an intimate thing. It’s you and the reader making these journeys. And you’ve got to keep them entertained and engaged, as you would if they were actually physically with you. If you’re not finding it interesting, then it’s not going to convince anyone else. You can’t fake it.

But wherever you go, if you know how and where to look and you look hard enough, there is always a reason to go there. It might be a person you meet; a story from history; or an old building that’s got a really good story.

Do you have to cut out stories you love, because they just won’t fit?

I did a chapter of little snippets in The Channel for that very reason, called Some Channel People. There were a few that I wish I could have talked about in greater depth. I found a couple of references in newspaper archives to a Jewish couple, Franz and Anna Nurvinski, who were found during the War, floating in the Channel in a dinghy, nearly starved. They’d fled from Germany.

They were questioned by the Home Office, who refused them sanctuary. So they were put back on the boat that picked them up and dropped off in Algiers, where they were taken into French custody. I found out that they were then put in separate cells, and Franz tried to hang himself. He thought he never see his wife again, and they would be sent back to Germany.

But then the trail went completely cold. They had quite an unusual name. I tried all different spellings and looked in all sorts of places, but I couldn’t find anything more about them. I didn’t want to leave it out altogether, so that ended up in that little chapter. But I’d love to have found out more.

I also found a story about an English woman who was murdered in Boulogne in the 1920s. She was on a day trip with a friend, she went into the bathroom at the ferry port, and she never came out again. They found her dead out on the dunes a couple of weeks later. The murder was never solved. Even now, 100 years on, we don’t know why May Daniels was killed, or who did it. And I couldn’t find a place for that. Sometimes you’ve got a really good story, but somehow you can’t fit it into the narrative.

Tell me about your writing routines. Do you have any rituals?

No rituals as such – other than panic! I love finding the stories. I love meeting people. And I love seeing the places. But when I come home and have to write it all up, I find it really hard. Without opening the gates on my personal hell, I don’t think I’m very good at it. So I try to try to put it off as long as possible.

I write in the spare bedroom, which is the darkest and coldest room in the house. We’re in a lower ground-floor flat, so there’s just a postage stamp of sky. I don’t come in strewing roses from my hatband, and thinking, ‘Brilliant! I’m going to spend the whole day writing.’

I sit down and think, ‘Right, I’m going to switch the computer on, open the document, and I’m going to get on with it. I’m going to get this writing done. The quicker you do it, the more time you can spend shaping it and revising it.’

Then I think, ‘Well, I’d better check my email first.’ I look, and there are a few things with links in, so I click them, and I think, ‘I’ll just read these, and then I’ll start.’

Then I think, ‘Well, I’ll have a quick look at Twitter in case anyone’s messaged me. I don’t want to miss anything.’ And before you know it, three hours have gone, and you haven’t done anything.

So I do find it hard. I meet people and they say, ‘You’re so lucky. I love writing! It would be my ambition to just write and write and write. And I think, ‘What, are you nuts? That sounds like hell!’

But if they get to write full-time, they do exactly what you’ve described. Because suddenly there’s a lot more at stake, a lot more fear involved.

Yes! So my routine basically consists of procrastinating. And it’s self-defeating, because you’ve got that constant, nagging anxiety that you’ve got a deadline to meet. Journalists I know just tear their hair out, because they say, ‘You get one deadline a year, and you still miss it!’ They’re writing three things a day. It is a luxury to have that time. In theory. But it never really works out like that.

I always end up feeling the book is rushed, and I should have spent more time on it. Then you send it off, and you think it’s going to come back and they’re going to say, ‘It’s hopeless, we can’t publish this. We want the advance back.’

Every time I send in a book manuscript, I hide for about three weeks. I don’t look at my emails, because I just dread what’s coming back. So far, it hasn’t been rejected. But that’s my routine: procrastinating, stressing and putting myself through the wringer with ridiculous levels of self-criticism and anxiety.

Do you ever get to a point where you’re just in flow while you’re writing?

When it happens, it’s brilliant. It just doesn’t happen very often. But there are times when I look at the word count, I think, ‘Blimey, where did that all come from?’ There are also days you’ll read something back and think, ‘This is the worst thing I’ve ever done! It’s like it’s written by a nine-year-old!’ Then the next day it’s not as bad as you thought, and you can see how to salvage it.

As well as choosing the right words and putting them in an agreeable order, rhythm is so important to writing. Especially with long-form writing like a book, because you’re trying to keep people’s attention for hours.

Particularly when you’re being funny. You’re really good at that: timing a little twist in a sentence perfectly.

Funnily enough, a couple of nights ago, I was thinking about exactly that. I was reading PG Wodehouse, and he was the master at that. It’s such a great feeling, as a reader, when you start a sentence and think, ‘Here we go: there’s going to be a great payoff!’ And you’re never disappointed with Wodehouse. He’s one of the greatest writers we’ve ever produced, and he doesn’t get the credit he deserves because he was a gag man. People who make us laugh are not taken seriously.

Is there a book about writing that you’d recommend?

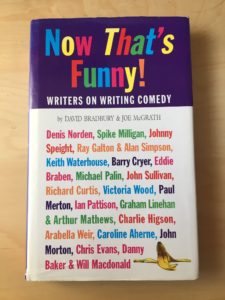

Stephen King’s On Writing is very good. But one I read a lot is Now That’s Funny. It came out in 1998, and it’s really hard to find now. I got it in a remainder shop in Greenwich for £2. They had a pile of about ten of them and I wish I bought them all, to give to people.

They just interview a load of comedy writers, and talk to them about what they do. What they find funny, writing that they really enjoy, and how they come up with the stuff they write. It’s mainly script writing and I’m not a comedy writer, so it’s not anything that I do. But I find it so inspiring.

It’s much more interesting and useful than someone telling you what you should do. I’ve written more than 20 books, and I still don’t know how to do it. I wouldn’t presume to tell people how to how to write a book. I can tell people how I do it. It might not be the best way, but it works for me.

You also have a podcast, Coastal Stories. Do you enjoy making something that’s more immediate, with no gatekeepers?

It’s so different to writing a book, which is a long, laborious process involving a lot of people. With the podcast, I keep it really simple. I go to the beach and record the sea, so listeners don’t just have my voice, unaccompanied. There’s the sound of the waves in the background. Then it’s just these short, standalone stories, told in about 15 minutes.

I’d done two or three of them when I suddenly thought, ‘I’ve written this, recorded it, edited it, posted it on the hosting site, and put it up on Twitter and Facebook – all in the same day. And I did all of it.’

I found it really liberating. I tend to write sweeping sentences that go on for far too long. And after the first couple of podcasts, I realised I was writing for a reader, rather than a voice. I’ve had to adapt the way I write to be read out loud, which was really interesting and useful.

It’s also is a way of me learning to trust myself. I don’t have massive amounts of confidence when it comes to writing, so I feel reassured that there are other people along the publishing process with big nets, ready to catch the rubbish stuff and correct it. With the podcast, it’s just me. It’s my words, my voice going out there.

The feedback has been really good. I’m never proud of things that I do. The only books I can say I’m really proud of are the ones I ghost-wrote for Bernard Sumner and AP McCoy. And that was because I wanted to do a good job for them and make their book really good.

With the podcast, I’ve learned to be proud of something. And that you can be proud of something without saying it’s the best thing ever. You don’t have to be boasting about it. I can’t see myself ever doing that! But I’ve done these 20 broadcasts that I’m proud of. I’m going to keep doing it. And hopefully people will still enjoy listening to it.

You should be proud of the books as well. Because they’re great. I loved The Channel!

I always think they could be better. When I look at this book, I see the bits I wish I’d done. I see the gaps.

As a coach, I hear that a lot. People say, the album’s fine, but there are two tracks that don’t quite work. Or, I’m really proud of this film, but my best scene got cut. Everybody can see what could be better, or what didn’t quite live up to their vision. Have you seen the proofs of Hard Times in the British Library? Dickens was still amending sentences, even after the books were published.

I used to work in the British Library quite a lot when I lived in London. Whenever I’d grind to a halt with what I was doing, I’d go down into the Treasures Gallery, where they display those manuscripts. I always remember Thomas Hardy’s handwritten manuscripts of Tess of the d’Urbervilles. At the top of the first page, it had The Daughter of the d’Urbervilles. The word ‘daughter’ been crossed out and ‘Tess’ written over the top. He’d changed the title, after he written it! That is quite reassuring.

Before it became The Great Gatsby, F Scott Fitzgerald tried a few titles. One that that was in the running till quite late, apparently, was Trimalchio in West Egg. It reassures me that that F Scott Fitzgerald thought that title was a goer for a very long time!

Which characters really stuck with you, when you’d finished The Channel?

Jabez Wolffe tried to swim the Channel 21 times, and failed every time. His first attempt was in 1907, and he was still trying in the late 1920s. At one point he got to within 800 yards of the French shore, and the tide turned and washed him back out again.

Yet still established himself as the greatest Channel swimming coach ever. He started coaching women swimmers particularly, and he had this bizarre opinion that brunettes would never be able to do it because they were too flighty. Apparently you need a good blonde, to swim the Channel, because they’re stickers. I just that he was the most insane, wonderful huge character. Just the fact that he’d failed all those times and he kept trying!

The other one was Laddie. Her name was Hilda Sharp but she was called Laddie because she had really short hair and boyish features. She was 19 when she first tried to swim the Channel. And she did it eventually, in 1928. She just struck me as out of her time: this incredible, independent, determined young woman who decided she wanted to swim the Channel because there was prize money on offer, and she wanted to move to Australia and buy a sheep farm.

She was a typist from Hither Green, which is near where I’m from in south-east London. I couldn’t get her into the book because I talked about Mercedes Blight and Trudy Edell, who were the two pioneering women swimmers.

But I developed a bit of a historical crush on Laddie Sharp, and I tried to find out what happened to her. She ended up in Chicago, where she married a man from Hull. But then the trail went cold. Although in one census in the 30s or 40s, she put her occupation down as swimmer, she was swimming coaching professionally, in America.

She trained in Deal, so when I swim in the Channel in the mornings, I often think of Laddie.

Sheryl Garratt is a writer and a coach helping creatives to get the success they want, making work they love. Want my free 10-day course on growing a creative business? Get it here.

Note: If you buy any of these books after clicking on the links above, I get a tiny payment from Amazon, that helps with the upkeep of the site. If you prefer to buy from independent bookshops, more power to you!

He’s touring the UK with his show about the shipping forecast. I’ve seen it – it’s brilliant!

Why isn’t Charlie writing for the New European anymore? I loved his insights into European and non-UK writing.

His love of translated works inspired me to read books I would have not even knew existed.

I have long been an admirer of his writing, although I listen on audible. He has a great human touch and connects with the reader/listener ver quickly.

Also love his range of topics, from the weather forecast to WG Grace in his final years?

Looking forward to his next one, so get your finger out Charlie.

I’ve loved his writing for many years. He is a wonderfully English voice, self-deprecating, affectionate and very funny. An irony fist in a velvet glove. (OK – that needs work…).

His culture/literature articles in The New European newspaper are always wonderfully researched and understatedly brilliant.

I love his books. Glad you like them too!

Oh Charlie what an interesting life you have. You are the type of person who won’t let go of a subject or a person you find intriguing. More power to your elbow! You are so lucky to be able to put into print what interests you and to make a living by it. I hope you write so many more books Charlie. Your greatest gift is you have your mum’s sense of humour which you weave into all your books.